“It’s not just the trim”

Growing rugged all terrain hooves requires more than just the right trim at the right time. It’s often been said that the trim accounts for only a quarter of the outcome and lifestyle accounts for three quarters. Hooves need nourishment through correct diet and stimulation through high mileage and exposure to conditioning terrain. Hoofcare needs to be holistic.

Diet

Any discussion about hooves and lifelong soundness must consider diet. Hooves are a product of nutrition, so if a horse’s diet is not right, its hooves will not attain optimal health nor become the strongest link in the equine chain. What’s more, hooves are a litmus test of inner health.

The equine hoof is metabolically very active tissue. It is designed to exist in a regime that is constantly replacing layers of worn away tissue and in a healthy horse it is constantly growing at the rate of about 10mm per month. This means it needs a constant supply of a range of nutrients to be the building blocks of new hoof. Most nutrients are in adequate supply but some may need to be supplemented, especially if the horse does not have access to pasture.

Diet does not need to be over-thought. Keep it simple and feed more of the good and less of the bad.

It should be easy enough to feed a horse like a horse, but equine nutrition has become the play thing of a rampant industry that is constantly re-inventing the wheel of new, better, best supplements.

The simple reason why things go wrong in hooves is that the diet of domestic horses is over-supplying both energy and protein, but lacking important minerals and vitamins; creating what is effectively a first world malnourishment. There is no shortage of feed and no starving horses; there is either too much feed or too much of the wrong nutrients and not enough of the right ones. In short, the diet of domestic horses is now far removed from that which they evolved with over millions of years.

Horses evolved to survive in a semi-arid environment with a brief spring and a long period with dry feed. Boom then bust; feast then famine.

Evolution gave them the ‘famine’ gene which allows them to produce body fat reserves that can be called upon in lean times. They are literally born insulin resistent. Fortunately, any flush of green feed in their natural environment was diluted by the tufty dry grass that new shoots had to grow through.

The equine digestive system is extremely efficient at retrieving all the possible nutrition from poor quality herbage and horses can literally run on the smell of an oily chaff bag. Mud fat is easy to achieve, but horses should definitely not be fat all year around. Instead, they should be maintained in a mid-range condition score with the slight hint of ribs, just like a human athlete.

Too much of the good life is going to eventually lead to the equine version of late onset diabetes which can progress to Cushing’s Syndrome.

Horses are “trickle feeders”, and they need to be eating small amounts often. Their stomach is very small in proportion to their body mass; no bigger than a football and should not be totally full or it does not function properly. Therefore, feeds should be limited to no more than 2 – 4 litres depending on the size of the horse. Small amounts often!

A horse’s stomach can become over acidic if it is not chewing high roughage feed, because saliva produced by chewing contains bicarbonate that placates acid.

Periods of starvation are also detrimental to digestive health due to unplacated acidity and also death of essential microbes in the hind gut.

What is a good equine diet that will promote hooves good enough for lifelong soundness?

The secret is to align diet with genetics; with the design of the species. Horses have quite a small stomach and a long intestinal tract that is engineered to have a constant throughput of high fibre, low quality herbage.

Don’t zone in on one aspect of nutrition, it is a broad subject.

Don’t zone in on one aspect of nutrition, it is a broad subject.

Cornerstone of the equine diet needs to be hay, and a lot of it, made the right way from the right grasses. Ideally this should be fed slowly over a long period of time every day (think slow hay feeders).

The right grasses growing at pasture come a close second.

Beware, however, that much of the hay and pasture available has been developed for cattle (production animals that are either fattened for slaughter at a young age or producing high yields of milk). Highly productive species such as ryegrass, clover or lucerne in temperate climates and buffel, kikuyu or lucerne in the tropics, are not suitable in the long term for horses. Horse friendly grass and hay is best derived from species that are less agriculturally desirable than these farmer favourites. That is, they are lower in sugar content.

Many horses that are not on an ideal mixed pasture and/or hay, (especially in high rainfall and coastal areas that have soils leached of minerals growing similarly deficient pastures), respond favorably to a complete hoof supplement.

When adding minerals to a horse’s diet, be aware that some minerals have a blocking effect on others, so the correct ratios must be added and the more you add of any individual mineral, the more you may need to add of others to keep ratios balanced.

As a further word of caution, be conservative with minerals and be careful not to over mineralize, especially with oxides and carbonates. There seems to be an increasing incidence of pathological mineral deposits (enteroliths, bladder stones etc) that may be linked to lavish usage of inorganic minerals especially magnesium oxide.

Don’t overlook the importance of a constant supply of water (fresh, not mineralized) and always have salt available.

Don’t rely on your horse’s opinion of what it would like to eat. Horses are notoriously fussy eaters and will over eat the wrong things.

Equine nutrition is a huge subject in itself and warrants further investigation. Fortunately there are numerous progressive internet sites with copious information. When doing your own research, use common sense and beware of who is selling what.

A major frustration for horse owners is that information regarding equine nutrition is often conflicting from one ‘expert’ to the next. A wise horseowner will regard the two-legged experts as mere tour guides who explain the science and offer solutions, but then seek the opinion that really matters; that of the four-legged experts.

Stay open minded, research the dietary parameters that seem to work best in your area (there is no better research than seeking out riders who are successfully growing healthy bare hooves). Monitor the progress of your horse’s hooves (be honest about it!) and tweak the diet where necessary, although if you alter the diet, only change one variable at a time.

High mileage

The best hooves to be found on domestic horses are not those trimmed by the best trimmers. It is miles under saddle that grows the best hooves. Of all the horses we see in our travels, it is the commercial trail horses and endurance horses that have the healthiest and strongest bare hooves. The extra mechanical stress generated by the weight of saddle and rider in combination with the sustained pressure of high mileage seems to produce the most robust, calloused hooves (of course, only if the hooves are functional).

Barefoot horses with ridden high mileage will always grow better hooves than horses with unmounted high mileage. So, ride your horse! Regularly.

On the other hand, it is a gross lack of meaningful movement that is the weakest link in the equine chain. Many domestic horses live in small paddocks on their own (effectively locked in solitary confinement) and are only ridden sporadically. This is the reality of modern urban life.

Some handy hints to maximize movement for domestic horses:

- Ride regularly (that’s an intentional repetition!)

- Keep horses in bigger mobs in bigger paddocks

- Change herd dynamics regularly.

- Keep the watering point distant from the feeding area and the salt lick distant from water.

- Use loop paddocks for feed restricted horses (fencing does not need to be expensive; a couple of strands of white hot tape and tread in ‘pig tails’ is usually adequate.)

- When feeding out hay, spread it as far apart as possible (ie. drive and feed out)

- If using slow feeders, instead of using a single large feeder, spread out many small ones.

Terrain

The terrain that a horse lives on plays a huge part in the quest to grow better hooves. This is passive conditioning using time as leverage; all the unridden hours when a horse is in its paddock.

Terrain needs to consider that horses belong in arid country and the tensile strength of keratin is highest when dry. Dry hooves are strong hooves, wet hooves are soft and subject to damage by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungus. Keep horses out of wet paddocks.

If dry paddocks are not available, then a night loafing area of dry footing such as 4-6 inches of pea sized river pebbles or natural gravel is ideal.

In areas that become a quagmire, products such as diamond mesh can be laid in gateways where horses congregate.

Further conditioning can be achieved by placing rough gravelly surfaces where horses are moving; the best place being where they get fed and are likely to discuss politics of the feeding hierarchy.

In swampy or sandy areas, it may be necessary to put down some road base fabric before any gravel, lest it disappears.

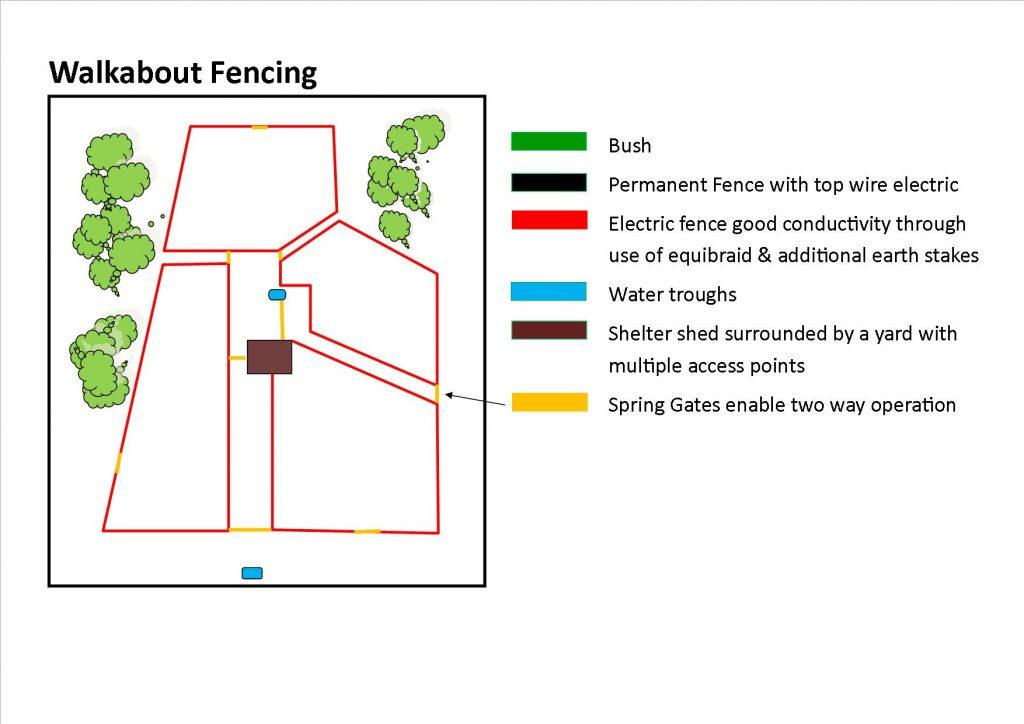

Walkabout fencing: Big mileage on small ground

(by Libby Franz, Equine Podiotherapist, Tasmania)

Many horses are challenged as barefoot mounts because they have sensitive hooves due to diet and laminitis seems to be a lifestyle condition of our domestic horse. The walkabout track enables us to limit the grass and control the diet, yet still have movement. A small sacrifice paddock may restrict the diet but it does not encourage movement.

Traditional ways of boarding and managing horses have contributed to the lack of hoof development and hence the need for shoes, so if we expect to develop a sound barefoot horse, then the lifestyle of the horse cannot be overlooked.

I developed a track system with my horses’ hooves primarily in mind, but there were multiple benefits for both horse and property that became apparent after boarding them this way for a number of years.

The original plan was to:

1) Control the diet

2) Create more movement

3) Manage the ground surface area

The starting point was a perimeter track around the entire boundary fence, trying to incorporate areas of bush and drier ground for the larger spaces, with the track kept narrow where it traversed good grass as the horses move far more quickly through narrow spaces.

To establish movement, hay was given at various points all around the track, which the horses soon started to use and developed their own paths through the bush areas.

This simple layout was further developed by the addition of extra tracks to the shelter shed, which opened up so many possibilities.

It is now possible to call all horses from where ever they are, to the shed, open all access points to the yard, mix individual feeds, then separate the horses to the different tracks with their own feed. They can all meet back up on the outer track, which they usually do at a water point. They usually head for water straight after a feed.

This “wagon wheel” design made it possible to control graze the pasture similar to cell grazing by opening the cells from the outer track creating more movement. This also improves the management and quality of pasture.

Each cell can be easily divided with “tread ins” to strip graze and further control pasture growth.

Spring gates allow the use of a battery powered gate release timer, enabling the horses to be allowed into an area or out of a confined space at a pre-set time.

As the horses are moved through the pasture without over grazing, there is no need to pick up manure and it can be harrowed in. If raked into piles on the track, the horses often set up stud piles making manure removal easier from these areas.

Horses have the ability to move to find shelter and shade when they need it. They also have enough space and the inclination to move enough to stay warm.

Large areas of electric fencing can easily be removed when hay is to be cut or pasture improved. Muddy areas can be avoided or road base put down.

With this new “walkabout” layout, I now no longer carry buckets or heavy bales of hay for more than a few metres and the time and energy I save can be put into quality time with my four legged family or should that be herd?!

by Libby Franz

Foal hoof development

Good hooves are made, not born. Equine hoof development starts the moment a foal stands on its wobbly legs, starting its life as a high mileage prairie wanderer. Endless horizons; no fences, harsh terrain and native herbage.

And then there are foals born to domestic life. Small paddocks, soft ground, improved pasture.

Domestic foals need help to achieve their genetic potential, maximising the proliferation of micro vessels in the caudal hoof, deveoping the thickest possible corium and optimising development of the cartilagenous caudal hoof sling. The closer we can align their domestic existence to their heritage, the better their hooves will develop.

For hoof development to keep pace with the growing body above, staying proportionately correct, thickening and toughening, hooves must be stimulated.

In practice, this means providing foals with the most possible movement. Ideally, foals should be kept in mobs, especially with other young stock. In addition foal hooves need to be regularly trimmed so the frog is always well grounded.

Maintenance trimming for horse owners

The secret behind amazingly healthy hooves is not who trims them, nor how good the professional trimmer is. Often there is not even a professional involved. Nor is it just about having the correct diet, adequate movement and the right environment (although these lifestyle factors certainly help).

The one factor above all else that seems to produce the best possible hooves is maintenance by the horse’s owner; a quick touch up with a rasp every 2 weeks.

This may sound a bit over-stated, but logical reasoning for such a claim can be found by rewinding 5000 years to the natural scheme of things before horses were domesticated. Back then, horses were prairie animals that covered great distances daily in search of grazing and water and freedom from predation. Life was tough.

Constant movement over harsh ground meant their hooves were continually getting worn down and to accommodate this, horses evolved to have rapidly growing hooves so they never wore down too much. Importantly, growth equalled wear and their hooves existed in a state of dynamic equilibrium. The hoof wall never grew too long beyond the sole, so the frog and sole remained weightbearing and the hooves fully functional. There were no overgrown walls acting as mechanical lever forces which compromised circulation or broke away and exposed inner tissues to pathogenic invasion. Hooves in their natural state were robust and tight units.

Fast forward to our modern domestic horses which are invariably confined to small paddocks and are no longer existing as prairie animals (despite carrying the same genetic blueprint). They are rarely worked often enough to create the amount of wear endured by the wild hoof. In fact, wear of the hooves is now exceeded by growth and when they grow long they become dysfunctional and mechanically weakened.

Traditional hoofcare has dealt with overgrowth by re-trimming hooves every 6-8-10 weeks (or when the trimmer could get there). Sometimes they are ignored until the overgrowth breaks off. But even if a horse owner has the foresight and resources to ensure their horses are never more than 4 weeks between trims, equine hooves simply cannot attain optimum health in this regime. They are meant to remain short and functional.

How can this storyline be improved?

What if a horse owner can mimic the constant trimming regime of the wild hoof by maintaining a horse’s hooves in between visits from their professional trimmer? In simple terms, pick up a hoof and keep the walls rolled and rounded with a rasp every fortnight.

What is stopping you from trying?

If maintenance trimming is as good as the author suggests, then why doesn’t everyone do it? Even though a large number of horse owners have taken it up and their horses’ hooves are better than ever, there is still a widespread misconception that it is too difficult a task, both physically and technically.

Yes it is physically hard, bending over and holding a heavy hoof steady whilst pushing a rasp across it, but maintenance trimming done often enough is only ever a small, brief job. It’s really not much harder than cleaning hooves out and can be quickly done when untacking after a ride. Anyone who is sound enough to get in the saddle should be able to handle a rasp long enough for maintenance trimming.

Yes it is physically hard, bending over and holding a heavy hoof steady whilst pushing a rasp across it, but maintenance trimming done often enough is only ever a small, brief job. It’s really not much harder than cleaning hooves out and can be quickly done when untacking after a ride. Anyone who is sound enough to get in the saddle should be able to handle a rasp long enough for maintenance trimming.

Maintenance trimming has been made even easier by the evolution of hoof stands that have a cradle which supports the upturned hoof and takes the weight of the horse out of the equation. Modern rasps are also incredibly sharp.

Horse owners also have the option of riding first and trimming second. If you ride before trimming, your whole body will be warmed up and loosened and ready to bend under your horse for trimming. In addition to this, if you ride on an abrasive surface before trimming – we call this the council trim – half the job is done for you.

But wait, there’s more – if you have a horse that is a bit too opinionated whenever its hooves are picked up and is pushing the limits of your fledgling leg handling abilities, a good old fashioned sweaty saddle cloth will always sort out bad behaviour! Again, ride first and trim second.

Maintaining equine hooves does not require a doctorate in equine sculpture. If you get well-schooled at a maintenance trimming workshop, you will learn to recognise the anatomical landmarks that allow you to read a hoof to objectively balance it and recognise the boundaries not to cross.

We are not talking here about the craft of shoeing which does take many years to master (the author can relate to this). Maintenance trimming is infinitely more simple than shoeing. It can be taught easily and objectively, especially if it is just maintenance in between professional trims.

You don’t need to be Yoda in a blue singlet to maintain a hoof.